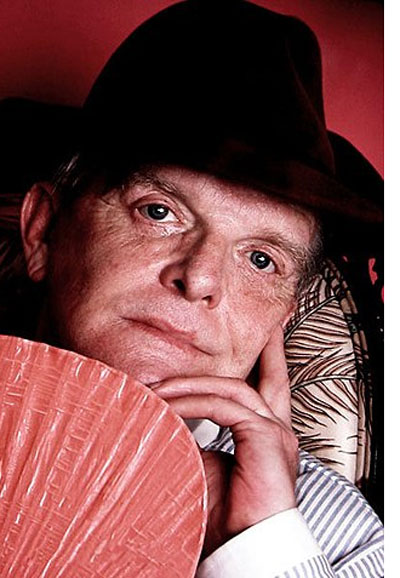

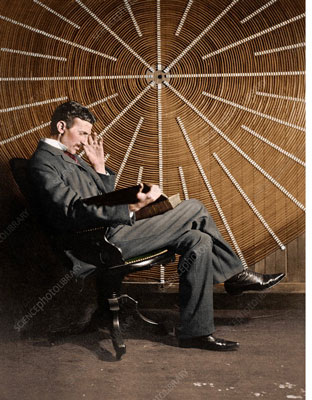

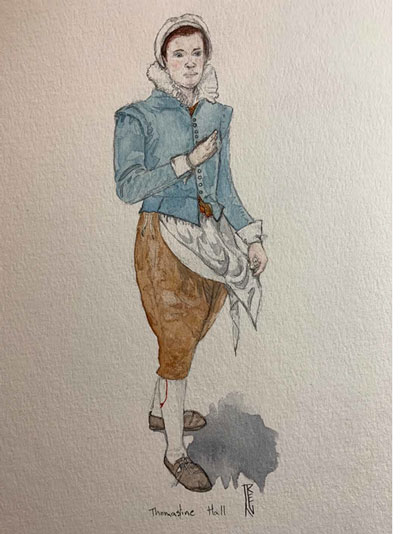

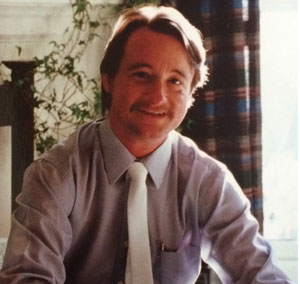

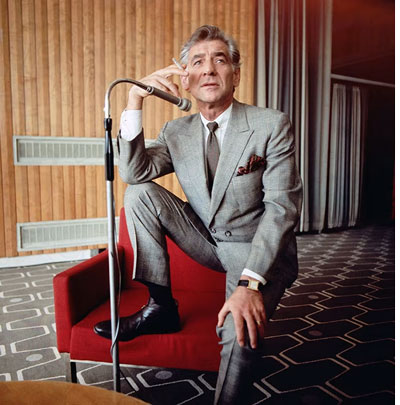

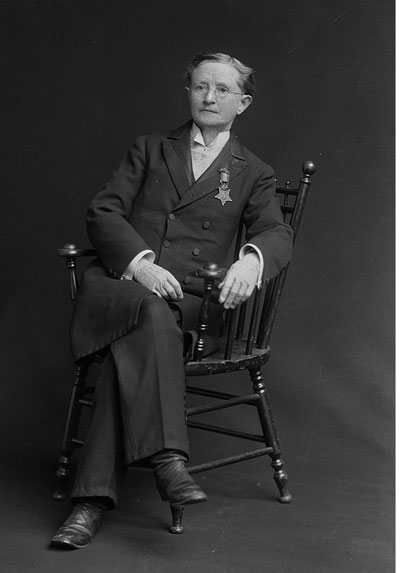

Kumu Hina (1972- ) | Marsha P. Johnson (1945-1992) | Harvey Milk (1930-1978) | Pauli Murray (1910-1985) | Kiyoshi Kuromiya (1943-2000) | Edna St. Vincent Millay (1892-1950) | James Baldwin (1924-1987) | Katharine Lee Bates (1859-1929) | Matthew Wayne Shepard (1976-1998) | Truman Garcia Capote (1924-1984) | Nikola Tesla (1856-1943) | Robina Fedora Asti (1921-2021) | Thomas(ine) Hall (c. 1603- post-1629) | Rachel Louise Carson (1907-1964) | Louis Graydon Sullivan (1951-1991) | Sally Kristen Ride (1951-2012) | Leonard Bernstein (1918 –1990) | Dr. Mary Edwards Walker (1832 -1919) | Bobby Holcomb (1947–1991) | Maude Ewing Adams Kiskadden (1872-1953) | Harris Glenn Milstead (1945 –1988) | Keith Haring (1958-1990) |

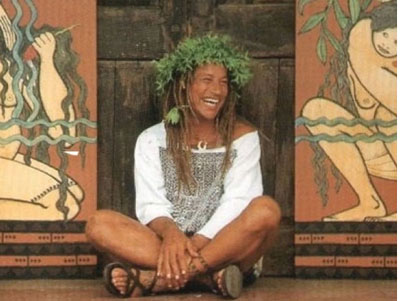

Kumu Hina is a Kānaka Maoli māhū– a traditional third-gender person who occupies "a place in the middle" between male and female – as well as a modern transgender woman. She is known for her work as a kumu hula, a filmmaker, an artist, an activist, and a community leader in the preservation and protection of ʻŌlelo Hawaiʻi and Kānaka Maoli culture. She is a fluent speaker of ʻŌlelo Hawaiʻi as well as several other Polynesian languages, including Tongan, Samoan, and Tahitian. She has been hailed as "a cultural icon," and has earned the respect and love of many by persevering in her efforts to always be a role model and earnest representative of the people of Hawai'i.

She attended Kamehameha School (1990) and the University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa (2004), where she began her activism career. One of three pioneer transgender women, Kumu Hina was a founder of the Kulia Na Mamo transgender health project in 2001, focusing on HIV/AIDS Prevention and Education in Hawai'i. She was the cultural director of Halau Lokahi Public Charter School for 13 years, dedicated to using native Hawaiian culture, history, and education as tools for developing and empowering the next generation of warrior scholars. In 2014, Hina announced her bid for a position on the board of the Office of Hawaiian Affairs, one of the first transgender candidates to run for statewide political office in the United States. She has also taught Hawaiian language at Leeward Community College and currently devotes her time to teaching Native Hawaiian and Pacific Islander men in incarceration in Hawaii. Kumu Hina is currently a cultural advisor and leader in many community affairs and civic activities, and she is in her 11th year of service to the community in her role as Chairperson and Kona moku representative for the O'ahu Island Burial Council, which oversees the management of Native Hawaiian burial sites and ancestral remains.

She was the subject of the feature documentary film Kumu Hina, directed by Dean Hamer and Joe Wilson. In 2020, she directed, produced, and narrated The Healing Stones of Kapaemahu, an animated short film based on the Hawaiian story of four legendary māhū who brought the healing arts from Tahiti to Hawai'i and imbued their powers in giant boulders that still stand on Waikiki Beach. Narrated in the rare Ni'ihau dialect of Hawaiian, the film premiered at the Tribeca Film Festival, winning the Grand Jury Award and being nominated for an Oscar. Kumu Hina is a recipient of the National Education Association Ellison Onizuka Human and Civil Rights Award, Native Hawaiian Community Educator of the Year, and a White House Champion of Change. USA Today named Wong-Kalu one of ten Women of the Century from Hawai'i. Kumu Hina is also featured in Naomi Hirada’s 2022 anthology We Are Here: 30 Inspiring Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders Who Have Shaped the United States, published by the Smithsonian Institute.

Marsha “Pay it No Mind” Johnson (1945-1992), is one of the most venerated icons in LGBTQ+ history.

Johnson was a Black trans woman who was a force behind the Stonewall Riots and surrounding activism that sparked a new phase of the LGBTQ+ movement in 1969. When she came out in 1966, Johnson initially used the moniker "Black Marsha" but later decided on the drag queen name "Marsha P. Johnson," getting Johnson from the restaurant Howard Johnson's on 42nd Street, stating that the P stood for "pay it no mind." She always used the phrase sarcastically when questioned about gender, saying "It stands for 'pay it no mind.'" She variably identified as gay, as a transvestite (the term transgender woman was not in broad use during her lifetime), and as a queen (referring to drag queen). In 1972's Out of the Closets: Voices of Gay Liberation, Johnson discussed being a Street Transvestite Action Revolutionary (STAR) and openly described her experiences of the dangers of working as a houseless street prostitute in drag.

Johnson's style of drag was not what we think of today as "high drag" or "show drag," due to her being unable to afford to purchase expensive clothing, makeup, and accessories. Instead, she received leftover flowers after sleeping under tables used for sorting flowers in the Flower District of Manhattan, and was known for wearing crowns of fresh flowers; she was tall, slender, and often dressed in flowing robes and shiny dresses, red plastic high heels and bright wigs. Most of her drag performance work was with groups that were grassroots and political, including the drag performance troupe Hot Peaches, from 1972 through the 1990s. In 1975, she was photographed by famed artist Andy Warhol, as part of his Ladies and Gentlemen series of Polaroids.

Though generally regarded as "generous and warmhearted" and "saintly" under the Marsha persona, an angry, violent side of her personality could sometimes emerge when she was depressed or under severe stress. When this happened, Johnson would often get in fights and wind up hospitalized and sedated, and friends would have to organize and raise money to bail Johnson out of jail or try to secure release from places like Bellevue Psychiatric Hospital. In the 1979 Village Voice article, "The Drag of Politics", by Steven Watson, other members of the gay community at the time explain that it was perhaps for this reason that other activists had been reluctant at first to credit Johnson for helping to spark the gay liberation movement of the early 1970s.

Johnson was one of the first drag queens to go to the now-famous Stonewall Inn after management began allowing women and drag queens inside; it was previously a bar for only gay men. In the early morning hours of June 28, 1969, the Stonewall Riots began after Stormé DeLarverie fought back against the police officer who attempted to arrest her that night, spawning a series of spontaneous protests by members of the gay community in response to the police raid, which had quickly become violent. The riots are widely considered the watershed event that transformed the gay liberation movement and the twentieth-century fight for LGBTQ+ rights in the United States.

Johnson has been named as being one of "three individuals known to have been in the vanguard" of the pushback against the police at the uprising. Famously, it has been claimed that Johnson threw a brick at a police officer, an account that has never been verified. However, many have corroborated that on the second night of the riots, Johnson climbed up a lamppost and dropped a bag with a brick in it down on a police car, shattering the windshield.

Following the Stonewall uprising, Johnson joined the Gay Liberation Front and marched in the first Gay Pride rally on June 28, 1970. Shortly after that, Johnson and close friend Sylvia Rivera co-founded the Street Transvestite Action Revolutionaries (STAR) organization. STAR House became one of the first shelters for homeless gay and trans youth, and the two queens paid the rent for it with money they made themselves as sex workers, providing food, clothing, emotional support, and a sense of family for the young drag queens, trans women, gender nonconformists, and other gay street kids living in the Lower East Side of New York. Johnson and Rivera became a visible presence at gay liberation marches and other radical political actions. A reporter at one of these gay rights rallies once asked Johnson why the group was demonstrating, and Johnson shouted into the microphone, "Darling, I want my gay rights now!"

Between 1980 and her death in 1992, Johnson lived with a friend, Randy Wicker, and when Wicker's lover, David, became terminally ill with AIDS, she became his caregiver. After visiting David and other friends with the virus in the hospital during the AIDS pandemic, Johnson, who was also HIV-positive, became committed to caring for the sick and dying, as well as doing street activism with AIDS activist groups, including ACT UP.

In 1992, "gay bashing" was an epidemic in New York. In 1992 alone, there were 1,300 reports of anti-LGBTQ+ violence, including many perpetrated by police. In response, marches were organized, and Johnson was one of the activists who marched in the streets, demanding justice. She had been speaking out against the "dirty cops" and elements of organized crime that many believed responsible for some of these assaults and murders, and had even voiced the concern that some of what Randy Wicker was stirring up, and pulling her into, "could get you murdered." Only weeks later, on July 6, 1992, Johnson's body was found floating in the Hudson River, a death initially ruled a suicide by the NYPD. At the time, several people came forward to say they had seen Johnson being harassed by a group of ruffians who had also robbed people; another witness saw a neighborhood resident fighting with Johnson on July 4 and reported that the individual had used a homophobic slur and had later bragged to someone at a bar that he had killed a drag queen named Marsha. All of these leads were dismissed and ignored by the NYPD.

Johnson's body was cremated and, following a funeral at a local church and a march down Seventh Avenue, friends released her ashes over the Hudson River, off the Christopher Street Piers. After the funeral, controversy and protest followed the case; following extensive lobbying by transgender activist Mariah Lopez, it was eventually re-opened in 2012 as a possible homicide. In 2016, Victoria Cruz of the Anti-Violence Project also addressed Johnson's case and succeeded in gaining access to previously unreleased documents and witness statements. Some of her work to find justice for Johnson was filmed by David France for the 2017 documentary The Death and Life of Marsha P. Johnson.

Marsha Johnson's death remains an open case, with the cause of death being listed as "undetermined." Her actions and words continue to inspire trans activism and resistance and will continue to do so well into the future.

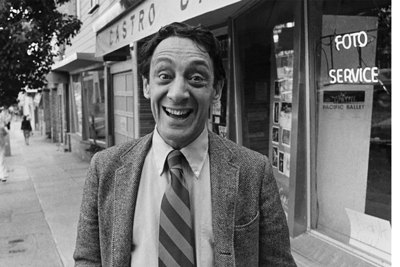

Harvey Milk (1930-1978), an American politician and the first openly gay elected official in the history of California.

Harvey Milk came from a small middle-class Jewish family that had founded a Jewish synagogue and was well known in the New York Jewish community for their civic engagement. He knew he was gay by the time he attended Bayshore High School, where he was a popular student with interests ranging from opera to playing football.

While at New York State College for Teachers (now State University of New York) in Albany, where he studied math and history, Milk penned a popular weekly student newspaper column where he openly addressed issues of cultural differenceswith a reflection on the lessons learned from World War II. After graduation, Milk joined the United States Navy during the Korean War. He served aboard the submarine rescue ship USS Kittiwake as a diving officer. He later transferred to Naval Station, San Diego, to serve as a diving instructor. In 1955, he resigned from the Navy at the rank of lieutenant, junior grade, forced to accept an "other than honorable" discharge and leave the service rather than face a court-martial after being officially questioned about his sexual orientation.

Following his Naval discharge, he began teaching at George W. Hewlett High School on Long Island. In 1956, he met Joe Campbell at the Jacob Riis Park beach, a popular location for gay men in Queens. Milk pursued Campbell passionately and they eventually began a committed relationship—one which would last six years.

After parting ways with Campbell, Milk thought of moving to Miami to marry a lesbian friend so that they would "have a front and each would not be in the way of the other.” However, he instead decided to remain in New York, where he secretly pursued many gay relationships, all of which were brief. In 1962, Milk became involved with Craig Rodwell. Though Milk courted Rodwell ardently, he was uncomfortable with Rodwell's involvement with the New York Mattachine Society, a gay-rights organization. When Rodwell was arrested for walking in Riis Park, and charged with inciting a riot and with indecent exposure (the law required men's swimsuits to extend from above the navel to below the thigh, which Rodwell's did not), he spent three days in jail. The relationship ended soon afterward as Milk became alarmed at Rodwell's tendency to agitate the police.

Milk traveled to San Francisco in 1969 with the Broadway touring company of Hair, for which his then-lover was the stage manager. Since the end of World War II, San Francisco had been home to a sizable number of gay men who had been expelled from the military and decided to stay rather than return to their hometowns and face ostracism. The city appealed so much to Milk that he decided to stay, working at an investment firm. In 1970, increasingly frustrated with the political climate after the U.S. invasion of Cambodia, Milk let his hair grow long. When told to cut it, he refused and was fired.

Over the next few years, Milk drifted from California to Texas to New York, without a steady job or plan. The time he spent with flower children during his travels wore away much of his conservatism. Milk met Scott Smith, and they began a relationship, with the pair moving to San Francisco. In March 1973, after a roll of film Milk left at a local shop was ruined, he and Smith opened a camera store on Castro Street, in the heart of the city’s growing gay community, with their last $1,000.

Milk became more interested in political and civic matters when he was faced with civic problems and policies he disliked. One day in 1973, a state bureaucrat entered Castro Camera, claiming that Milk owed $100 as a deposit against state sales tax. Milk was incredulous and traded shouts with the man about the rights of business owners; after he complained for weeks at state offices, the deposit was reduced to $30. Milk also fumed about government priorities when a teacher came into his store to borrow a projector because the equipment in the schools did not function. Later in 1973, two gay men tried to open an antique shop nearby, but the local Merchants Association attempted to prevent them from receiving a business license. Milk and a few other gay business owners founded the Castro Village Association, a first-in-the-nation organizing of predominantly LGBTQ businesses, with Milk as president. He organized the Castro Street Fair in 1974 to attract more customers to area businesses. Its success made the Castro Village Association an effective power base for gay merchants and a blueprint for other LGBTQ communities in the US. Milk decided that the time had come to run for public office. He said later, "I finally reached the point where I knew I had to become involved or shut up.”

Milk had drifted through life up to this point, but he found his vocation in politics. At first, his inexperience showed. He tried to manage without money, support, or staff, and instead relied on his message of sound financial management, promoting individuals over large corporations and government. He supported the reorganization of supervisor elections from a citywide ballot to district ballots, which was intended to reduce the influence of money and give neighborhoods more control over their representatives in city government. He also ran on a culturally liberal platform, opposing government interference in private sexual matters and favoring the legalization of marijuana. Milk's fiery, flamboyant speeches and savvy media skills earned him a significant amount of press during the 1973 election, but he was not elected. In 1975, he ran again for the combined San Francisco City/County supervisor seat and narrowly lost.

By now, he was established as the leading political spokesman for the Castro’s vibrant gay community. In 1975, state senator George Moscone, who had been instrumental in repealing the sodomy law earlier that year in the California State Legislature, was elected mayor of San Francisco. He acknowledged Milk's influence in his election by visiting Milk's election night headquarters, thanking Milk personally. In one of Moscone's first acts as mayor, he appointed a police chief who made it clear that gay police officers would be welcomed in the department, against the wishes of the department but with the mayor's blessing; this became national news.

Milk's role as a representative of San Francisco's gay community expanded during this period. On September 22, 1975, a former Marine prevented the assassination of visiting President Gerald Ford by Sara Jane Moore. That former Marine was Oliver Sipple, whom Milk had known well in New York. On psychiatric disability leave from the military, Sipple refused to call himself a hero and did not want his sexuality disclosed. Milk, however, took advantage of the opportunity to illustrate his cause that the public perception of gay people would be improved if they came out of the closet. He told a friend: "It's too good an opportunity. For once we can show that gays do heroic things, not just all that ca-ca about molesting children and hanging out in bathrooms.” Milk contacted The San Francisco Chronicle, and exposed Sipple as gay. Although he had been involved with the gay community for years, even participating in Gay Pride events, Sipple sued the Chronicle for invasion of privacy. President Ford sent Sipple a note of thanks for saving his life, to which Milk responded that Sipple's sexual orientation was the reason he received only a note, rather than an invitation to the White House.

Milk was appointed to the Board of Permit Appeals in 1976, making him the first openly gay city commissioner in the United States. He soon filed candidacy papers for the state assembly but lost. In 1977, however, he easily won election as a San Francisco City-County Supervisor, and was inaugurated on January 9, 1978. This was an important symbolic victory for the LGBTQ community, as well as a personal triumph for Milk. His election made national and international headlines.

A commitment to serving a broad constituency, not just LGBTQ people, helped make Milk an effective and popular supervisor. His ambitious reform agenda included protecting gay rights—he sponsored an important anti-discrimination bill—as well as establishing day care centers for working mothers, the conversion of military facilities in the city to low-cost housing, reform of the tax code to attract industry to deserted warehouses and factories, and other issues. He was a powerful advocate for strong, safe neighborhoods, and pressured the mayor’s administration to improve services for the Castro such as library services and community policing. In addition, he spoke out on state and national issues of interest to LGBTQ people, women, racial and ethnic minorities, and other marginalized communities.

One of these was a California ballot initiative, Proposition 6, which would have mandated the firing of gay teachers in the state's public schools—as well as the firing of any public school employees who supported gay rights. Proponents maintained that homosexual teachers wanted to abuse and recruit children. Milk responded with statistics compiled by law enforcement, providing evidence that pedophiles identified primarily as heterosexual. Attendance swelled at gay pride marches in San Francisco and Los Angeles as Milk and others campaigned against Proposition 6.

In one of his eloquent speeches, Milk spoke of the American ideal of equality, proclaiming, “Gay people, we will not win our rights by staying quietly in our closets. … We are coming out to fight the lies, the myths, the distortions. We are coming out to tell the truths about gays, for I am tired of the conspiracy of silence, so I’m going to talk about it. And I want you to talk about it. You must come out.” With strong, effective opposition from Milk and others, Proposition 6 was defeated at a time when many other political attacks on gay people were being successfully waged all around the US.

Milk's energy, affinity for practical jokes and humor, and unpredictability at times exasperated Board of Supervisors President, Dianne Feinstein. Milk also became Mayor Moscone's closest ally on the Board of Supervisors. Milk was often willing to vote against Feinstein and other more tenured members of the board. In one controversy early in his term, Milk agreed with fellow Supervisor Dan White, whose district was located two miles south of the Castro, that a mental health facility for troubled adolescents should not be placed there. After Milk learned more about the facility, he decided to switch his vote, ensuring White's loss on the issue—a particularly poignant cause that White championed while campaigning. White did not forget it.and went on to oppose every initiative and issue Milk supported.

Milk sponsored a bill banning discrimination in public accommodations, housing, and employment on the basis of sexual orientation. The City Supervisors passed the bill by a vote of 11–1, with White's the sole opposing vote, and it was signed into law by Mayor Moscone, using a light blue pen purchased for him by Milk especially for the occasion.

Given the hatred directed at gay people in general and Milk in particular—he received daily death threats—he was aware of the likelihood that he may well be assassinated. He recorded several versions of his will to be read in the event of his assassination. One of his tapes contained the now-famous statement, “If a bullet should enter my brain, let that bullet destroy every closet door.”

White resigned his position on November 10, 1978. Moscone planned to announce White's replacement on November 27. A half hour before the press conference, White avoided metal detectors by entering City Hall through a basement window and went to Moscone's office, where witnesses heard shouting followed by gunshots. White shot Moscone in the shoulder and chest, then twice in the head. White then quickly walked to his former office, reloading his police-issue revolver with hollow-point bullets along the way, and intercepted Milk, asking him to step inside for a moment. Dianne Feinstein heard gunshots and called police; she then found Milk face down on the floor, shot five times, including twice in the head. Soon after, she announced to the press, "Today, San Francisco has experienced a double tragedy of immense proportions. As President of the Board of Supervisors, it is my duty to inform you that both Mayor Moscone and Supervisor Harvey Milk have been shot and killed...." That night, a crowd of thousands spontaneously came together on Castro Street and marched to City Hall in a silent candlelight vigil that has been frequently cited as one of the most eloquent responses to violence that a community has ever expressed.

Milk’s assassin was acquitted of murder charges and given a mild reduced sentence for voluntary manslaughter, partly as a result of what became known as the “Twinkie Defense.” His attorney claimed that White had eaten too much junk food on the day of the killings and thus could not be held accountable for his crimes. White was sentenced on May 21, 1979—the day before what would have been Milk’s 49th birthday—igniting what came to be known as the White Night Riots. Enraged citizens stormed City Hall and rows of police cars were set on fire. The city suffered property damage and police officers retaliated by raiding the Castro, vandalizing gay businesses, and beating people on the street.

In total, White served just over five years for the double homicide of Moscone and Milk; he was released from prison on January 7, 1984. On October 21, 1985, he was found dead in a running car in his ex-wife's garage, having committed suicide by carbon monoxide poisoning.

As a result of White's trial, California voters changed state law to reduce the likelihood of acquittals of accused who knew what they were doing but claimed their capacity was impaired. Diminished capacity was abolished as a defense to a charge, but courts allowed evidence of it when deciding whether to incarcerate, commit, or otherwise punish a convicted defendant.

The life and career of Harvey Milk have been the subjects of an opera as well as many books and films. These include the biography The Mayor of Castro Street (1982); the 1984 Oscar-winning documentary The Times of Harvey Milk; and the 2008 drama Milk, which received eight Academy Award nominations, winning in two categories: Sean Penn was named best actor for his performance in the title role, and Dustin Lance Black won for his screenplay. A statue of Milk was unveiled in the center rotunda at San Francisco City Hall in 2008. On August 12, 2009, his nephew, Stuart Milk, accepted the posthumously awarded Medal of Freedom from President Barack Obama, who praised Milk’s “visionary courage and conviction” in fighting discrimination. The non-fiscal Harvey Milk state holiday (his birthday, May 22) was passed by the California State Legislature in 2009 and signed into law by then-Governor Arnold Schwarzenegger. Milk’s day is observed with events across the nation and around the globe. In 2012, San Diego named the street that leads to the doors of that city’s LGBTQ center Harvey Milk Street, and Long Beach dedicated the Harvey Milk Oceanside Promenade and Park. In 2014, the White House, the United States Postal Service, and the Harvey Milk Foundation hosted a historic first day of issuance ceremony at the White House for the USPS Harvey Milk Forever Stamp, marking the first time that an openly LGBTQ official joined the limited number of “great and accomplished Americans to grace the corner of an envelope and represent the US to the world.”

Harvey Milk was included in Time magazine’s list of the 100 most important people of the 20th century. He believed that government should represent individuals, not just corporate interests, and should ensure equality for all citizens while providing needed services. He spoke for the participation of LGBTQ people and other minorities in the political process. The more gay people came out of the closet, he believed, the more their families and friends would support protections for their equal rights. In the years since Milk’s assassination, public opinion has shifted on gay marriage, gays in the military, and other issues, and there have been hundreds of openly LGBTQ public officials in America, yet the work continues.

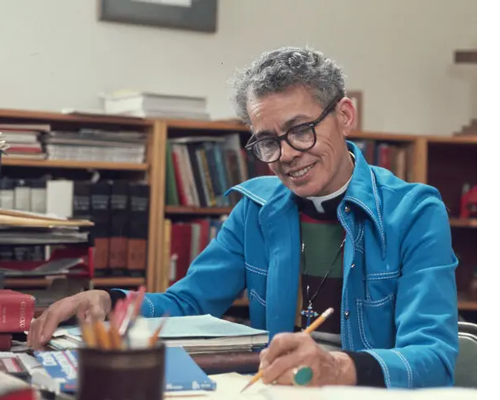

Pauli Murray (1910 – 1985), an American civil rights activist, advocate, legal scholar and theorist, author and poet, and--later in life--Episcopal priest and, posthumously, saint.

(According to the Pauli Murray Center, several scholars have explored Murray’s personal journals and writings and examined Murray’s relationship to their gender/s. Scholars have variably used “he/him/his” pronouns, “they/them/theirs” pronouns, “s/he” pronouns, and “she/her/hers” pronouns. Murray self-described as a “he/she personality,” so today’s article will follow that practice.)

Anna Pauline Murray was born in Baltimore, Maryland, on November 20, 1910, the fourth of six children of Agnes and William Murray. Agnes died of a cerebral hemorrhage in 1914. William suffered from depression exacerbated by the long-term effects of typhoid fever and was eventually confined at Crownsville State Hospital for the Negro Insane, where he was bludgeoned to death by a white guard with a baseball bat in 1923. Essentially orphaned after Agnes’ death, Murray was sent to live with his/her aunt, Pauline Fitzgerald Dame, and his/her grandparents, Robert George and Cornelia Smith Fitzgerald, in Durham, North Carolina.

At age 16, Murray moved to New York City to finish high school and then attend Hunter College, graduating from Hunter with a Bachelor of Arts degree in English in 1933, and changing his/her birth name to “Pauli.” During his/her undergraduate career, Murray had married William Roy Wynn, known as Billy Wynn, in secret on November 30, 1930, but quickly came to regret the decision. As Murray explained in notes to him/herself a few years later, he/she had felt repelled by the act of sexual intercourse. Part of him/her had wanted to be a "normal" woman, but another part resisted. "Why is it when men try to make love to me, something in me fights?" she wondered. Murray and Wynn only spent a few months together before both left town separately; they did not see one another again until Murray contacted him to have their marriage legally annulled in 1949.

Murray further continued his/her education at Jay Lovestone's New Workers School in New York, taking night classes on many subjects, including Marxist philosophy, historical materialism, Marxian economics, and problems of Communist organization. Throughout the 1930s, Murray actively questioned his/her gender and sex. He/she repeatedly asked various physicians for testosterone hormone therapy and exploratory surgery to investigate his/her reproductive organs, believing that he/she may have been intersex and had undescended testis, but he/she was repeatedly denied gender-affirming medical care throughout his/her lifetime. Murray always adopted androgynous dress, preferring pants to skirts, had a short hairstyle, and in fact often passed as a boy throughout his/her youth and 20s. He/she preferred to describe him/herself as having an "inverted sex instinct" that caused him/her to behave as a man would when attracted to women. He/she wanted a "monogamous married life,” but one in which he/she was in a man's role. The majority of his/her relationships were with women he/she described as "extremely feminine and heterosexual.” There is little doubt that throughout his/her lifetime, widespread homophobia and transphobia, and federal and state policies, severely constrained Pauli Murray’s ability to publicly or even privately explore his/her gender identity and sexuality thoroughly.

Murray took a job selling subscriptions to Opportunity, an academic journal of the National Urban League, a civil rights organization based in New York City. Poor health forced him/her to resign, and a doctor recommended that Murray seek a healthier environment, so Murray took a position at Camp Tera, a "She-She-She" conservation camp. Established at the urging of First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt, these federally-funded camps provided employment to young women while improving national infrastructure. During three months at the camp, Murray's health recovered. He/she also met Eleanor Roosevelt for the first time, the beginning of what became a lifelong friendship. Unfortunately, Murray clashed with the camp's director, who had found a Marxist book from a Hunter College course among Murray's belongings and disapproved of Murray's cross-racial relationship with Peg Holmes, a white counselor at the camp. Murray and Holmes left the camp together in February 1935.

In 1938, Murray began a media and letter-writing campaign to enter the PhD in sociology program at the all-white University of North Carolina. Despite a lack of support from the NAACP, Murray’s campaign received national publicity, although it was ultimately unauccessful. A member of the Fellowship of Reconciliation, Murray also worked to end segregation on public transport. In 1940, he/she sat in the whites-only section of a Virginia bus with Adelene McBean, his/her roommate and girlfriend. Inspired by a conversation they had been having about Gandhian civil disobedience, the two women refused to return to the rear, even after the police were called. They were arrested, jailed, and convicted of disorderly conduct. The Workers' Defense League (WDL), a socialist labor rights organization that also was beginning to take civil rights cases, paid their fines, and a few months later, the WDL hired Murray for its administrative committee; Murray subsequently became involved in the civil rights movement. At the same time, he/she worked as a teacher at the New York City Remedial Reading Project. He/she wrote many articles and poems, some of which were published in various magazines, including Common Sense and The Crisis.

Murray enrolled in the Howard University Law School in 1941, with the intention of becoming a civil rights lawyer; he/she was the only woman in the class. The following year, he/she joined George Houser, James Farmer, and Bayard Rustin to form the nonviolence-focused Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) and published an article, "Negro Youth's Dilemma," that challenged segregation in the US military. He/she also participated in sit-ins challenging several Washington, DC, restaurants with discriminatory seating policies. These activities foreshadowed the more widespread sit-ins during the civil rights movement of the 1950s and 1960s.

Murray was elected chief justice of the Howard Court of Peers, the highest student position at Howard, and in 1943, published two important essays on civil rights: “Negroes Are Fed Up” in Common Sense, and an article about the Harlem race riot in the socialist newspaper, New York Call. His/her most famous poem, “Dark Testament,” was also written that year. It was at Howard that he/she also became acutely aware of the oppression he/she faced as a Black person perceived as a woman, coining the term “Jane Crow” to describe the experience. Murray graduated first-in-class in 1944, winning the coveted Rosenwald Fellowship. Traditionally, the Fellowship was for graduate work at Harvard University, but Harvard Law did not accept women at that time. Murray was thus rejected, despite a letter of support from sitting President Franklin D. Roosevelt. Murray wrote in response to the decision, "I would gladly change my sex to meet your requirements, but since the way to such change has not been revealed to me, I have no recourse but to appeal to you to change your minds. Are you to tell me that one is as difficult as the other?" However, rejected again, Murray instead went on to earn a Master of Laws degree at the University of California, Berkeley, with a master’s thesis titled The Right to Equal Opportunity in Employment, which argued that "the right to work is an inalienable right.” After passing the California bar exam in 1945, Murray was hired as the state's first Black deputy attorney general in January of the following year. That year, the National Council of Negro Women named her its "Woman of the Year" and the feminist Mademoiselle magazine did the same in 1947.

Murray returned to New York City and provided support to the growing civil rights movement. His/her book, States’ Laws on Race and Color, was published in 1951 thanks to the United Methodist Women, who commissioned this work as a service to the movement and part of their Charters for Racial Justice. Thurgood Marshall, then-Chief Counsel of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) and later an Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States, described the book as the “Bible” for civil rights litigators. In the early 1950s, Murray, like many Black citizens involved in the civil rights movement, was targeted by McCarthyism. In 1952, he/she lost a US State Department post at Cornell University because the people who had supplied her references (including Eleanor Roosevelt, Thurgood Marshall, and trade unionist and civil rights activist A. Philip Randolph) were considered “too radical.” He/she was told in a letter that the university's regents had decided to give “one hundred percent protection” to the university “in view of the troublous times in which we live.”

In 1956, Murray published Proud Shoes: The Story of an American Family, a biography of how white supremacy and anti-Blackness oppressed his/her grandparents and their efforts to create racial uplift for their family, and a poignant portrayal of his/her hometown of Durham. Shortly after the book came out, Murray was offered a job in the litigation department at a new law firm, Paul, Weiss, Rifkin, Wharton, and Garrison. Murray was the first Black woman hired by the firm as an associate attorney, working there from 1956 to 1960. He/she first met Ruth Bader Ginsburg there, when Ginsburg was briefly a summer associate. Also while working there, Murray met Irene Barlow, the office manager at the firm. The two remained life partners until Barlow’s death in 1973.

In 1960, Murray traveled to Ghana to explore his/her African cultural roots and teach law. While there, he/she co-authored a book, The Constitution and Government of Ghana, with Leslie Rubin. When Murray returned to the U.S., he/she enrolled at Yale Law School to pursue the JSD degree and mentored several young women activists, including Marian Wright Edelman, Eleanor Holmes Norton, and Patricia Roberts Harris, who all became leaders in their own right.

President John F. Kennedy appointed Murray to the 1961–1963 Committee on Civil and Political Rights as a part of his Presidential Commission on the Status of Women. In the early 1960s, Murray worked closely with A. Philip Randolph, Bayard Rustin, and Martin Luther King, Jr., but he/she was critical of the way that men dominated the leadership of these civil rights organizations. In August 1963, he/she wrote to Randolph and asserted that he/she had “been increasingly perturbed over the blatant disparity between the major role which Negro women have played and are playing in the crucial grass-roots levels of our struggle and the minor role of leadership they have been assigned in the national policy-making decisions.” In a speech, "The Negro Woman in the Quest for Equality,” Murray criticized the fact that in the 1963 March on Washington, no women were invited to make any of the major speeches or to be part of its delegation of leaders who went to the White House, among other grievances.

In 1964, Murray prepared a memo entitled "A Proposal to Reexamine the Applicability of the Fourteenth Amendment to State Laws and Practices Which Discriminate on the Basis of Sex Per Se," which argued that the Fourteenth Amendment forbade sex discrimination as well as racial discrimination, in support of the National Women's Party's successful effort to add "sex" as a protected category in the Civil Rights Act of 1964. In 1965, Murray published her landmark article (coauthored by Mary Eastwood), "Jane Crow and the Law: Sex Discrimination and Title VII", in the George Washington Law Review. The article discussed Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 as it applied to women, and drew comparisons between discriminatory laws against women and Jim Crow laws. The memo was shared with every member of Congress and Lady Bird Johnson, then First Lady, who brought it to President Lyndon B. Johnson's attention.

In 1965, Murray became the first African American to receive a Doctor of Juridical Science degree from Yale Law School, with a dissertation titled Roots of the Racial Crisis: Prologue to Policy. Subsequently, he/she joined with Betty Friedan and others to found the National Organization for Women (NOW) in 1966, but eventually moved away from a leading role because s/he did not believe that NOW appropriately addressed the issues of Black and working-class women. Later in 1966, she and Dorothy Kenyon of the ACLU successfully argued a case in which a three-judge court of the United States District Court for the Middle District of Alabama ruled that women had an equal right to serve on juries. When future Supreme Court Associate Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg, then with the ACLU, wrote her brief for Reed v. Reed, which won a landmark SCOTUS decision establishing that the administrators of estates cannot be named in a way that discriminates between sexes, she added Murray and Kenyon as coauthors, in recognition of her debt to their work.

Murray served as vice president of Benedict College from 1967 to 1968. She left Benedict to become a professor at Brandeis University, where he/she taught from 1968 to 1973, receiving tenure in 1971 as a full professor in American Studies and appointed as Louis Stulberg Chair in Law and Politics. In addition to teaching law, Murray introduced classes on African-American studies and women's studies, both firsts for the university. He/she also published a collection of poetry, Dark Testament and Other Poems, in 1970.

Following his/her partner’s death in 1973 and increasingly inspired by his/her connections with women in the Episcopal Church, Murray left Brandeis to attend General Theological Seminary, where he/she received a Master of Divinity in 1976 with the thesis, Black Theology and Feminist Theology: A Comparative Review. He/she was ordained to the diaconate in 1976, and, in 1977, became the first African-American woman ordained as an Episcopal priest, one of the first generation of Episcopal women priests.

On July 1, 1985, Murray died of pancreatic cancer in the house she owned with lifelong friend Maida Springer Kemp in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. His/her autobiography, Song in a Weary Throat: An American Pilgrimage, was published posthumously in 1987. The book was re-released as Pauli Murray: The Autobiography of a Black Activist, Feminist, Lawyer, Priest, and Poet in 1987, and was republished under its original title with a new introduction in 2018.

Murray’s personal struggle with gender identity shaped his/her life as a civil rights pioneer, legal scholar, and feminist. While he/she lived openly in lesbian relationships for much of his/her later life, Murray’s career, Communist politics, and respectability politics shut down his/her options at a time when, in efforts to survive and maintain employment and housing, many gender-nonconforming people were forced to repress or conceal their identities. As biographer Naomi Simmons-Thorne writes, “Given the rigid enforcement of the gender binary, we do not, nor will we ever know, Murray’s true gender identity." What we do know, however, is that Rev. Dr. Pauli Murray's work greatly influenced the civil rights movement, expanded legal protection for gender equality, and inspired many others who followed her in the legal profession, academia, and the Episcopal church.

In 2012, the General Convention of the Episcopal Church voted to honor Murray as one of its Holy Women, Holy Men, commemorated on July 1, the anniversary of his/her death, along with fellow writer Harriet Beecher Stowe. In 2018, Murray was made a permanent part of the Episcopal Church's calendar of saints.

In 2015, the National Trust for Historic Preservation designated Murray’s childhood home as a National Treasure. In December 2016, the Pauli Murray Family Home was designated as a National Historic Landmark by the US Department of Interior.

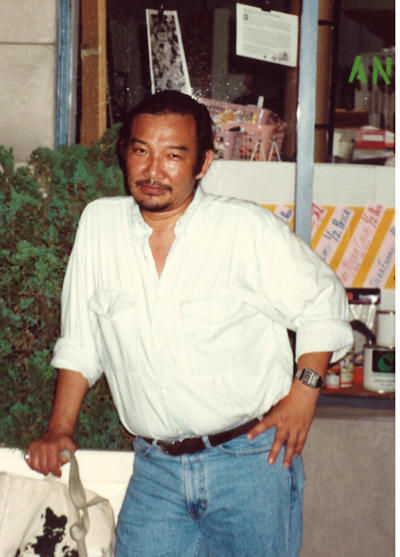

Kiyoshi Kuromiya (1943 –2000) was a Japanese-American civil rights, anti-war, gay liberation, and HIV/AIDS activist.

Kiyoshi Kuromiya was born on May 9, 1943, to California-born Nisei parents in Wyoming at the Heart Mountain Internment Camp, to which his family had been forcibly relocated from Monrovia, California, where Kuromiya later grew up, primarily attending white schools in the Los Angeles suburbs. (In 1983, Kuromiya visited the Camp with his mother, which he later recalled as being a formative experience for him as an activist.) By the early 1950s, he was using the name “Steve” instead of his given name, although in later life he returned to using his birth name.

He came out as gay to his parents when he was roughly 8 or 9 years old, at which time he was already fairly sexually active. He was arrested in a public park with a 16-year-old boy for lewdness around this time and was put in juvenile hall for three days as punishment, with an additional court order demanding that he receive hormone treatments from a glandular specialist, an early attempt at conversion therapy. In addition to increasing his already-active sex drive and causing his voice to break soon afterwards, the incident left him with a feeling of shame and perversion. Kuromiya remembered the treatments as “a traumatic experience, partly because I didn’t know exactly what they were doing to me at the time.” He later mentioned in a 1997 interview that his being arrested made him feel like a sort of criminal without knowing it, and left him with a feeling of shame that forced him to be secretive about his sex life—even early on. At the time, he did not know any of the terminology due to a lack of literature—he had never heard the word gay and didn't know what a homosexual was. As a result, Kuromiya utilized the Monrovia Public Library to try to learn more about the identity that he knew "was very important to him."

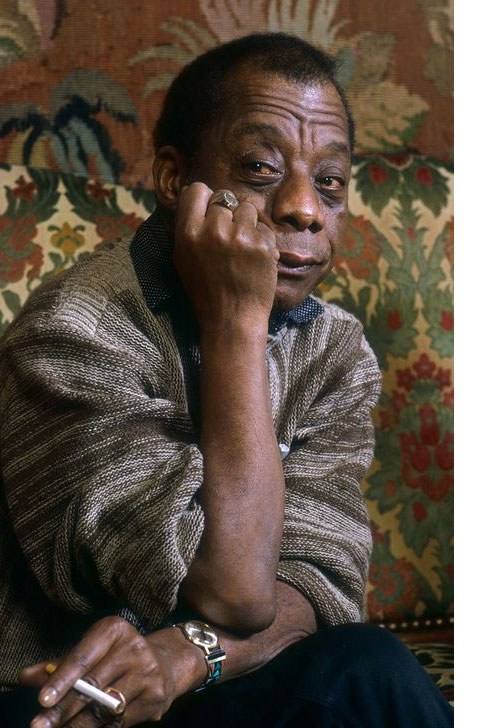

In 1961, Kuromiya decided to leave the West Coast to go to college in Philadelphia to study architecture at the University of Pennsylvania as one of six Benjamin Franklin National Scholars; the large scholarship covered almost all of the associated costs of attending. Kuromiya rarely attended classes, finding them “an incredible waste of time,” subpar to his high-school education. Instead, he immersed himself in creating and publishing a collegiate guidebook to greater Philadelphia’s restaurant scene—the book’s sales provided him with a substantial income—and activism. The University of Pennsylvania was very closeted at the time, but Kuromiya found other outlets for activism. In 1962, he participated in the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) Maryland diner sit-ins, and he was in attendance at the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom on August 28, 1963, not far from Martin Luther King Jr. during his "I Have a Dream" speech; Kuromiya met King, along with Rev. Ralph Abernathy and James Baldwin, later that night, and he continued to work closely with the reverend throughout the civil rights movement.

In 1965, Kuromiya and other activists took over Independence Hall in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania—calling it the Freedom Hotel, in support of people injured at Pettus Bridge in Selma during the March 7 “Bloody Sunday” civil rights march from Selma to Montgomery in Alabama. A week later, on March 13, 1965, after traveling to Montgomery to assist Dr. King, Kuromiya, along with Dr. King, Rev. Fred Shuttlesworth, and James Forman, were attacked by sheriff’s deputies and their volunteer crew while leading a group of Black high-school students on a voter registration march to the state capitol building The incident left Kuromiya bloodied and in need of 20 stitches to mend his head wounds. Though initially thought dead, due to the police attempts to cut off information about his condition, he was able to contact the media after gaining assistance from a gay hospital attendant. The following day, he confronted the county’s presiding officer, Sheriff Mac Sim Butler, alongside King, Foreman, John Lewis, and Rev. Ralph Abernathy. After falsely accusing Kuromiya of attacking an officer with a knife, Butler recanted and apologized, which, according to King, “was the very first time a southern sheriff had apologized for injuring a civil rights worker.” As a sign of atonement, Butler signed a statement prepared by King and Kuromiya and “disbanded the sheriff’s volunteer posse,” a group of vigilantes on horseback associated with the White Citizens Council. The next day, President Johnson deputized Alabama’s national guard to protect the march from Selma to Montgomery. On April 4, 1968, following Dr. King’s assassination, Kuromiya helped care for the King children, Martin III and Dexter, in Atlanta during the week of the funeral.

Kuromiya publicly came out as gay on July 4, 1965, at the first Independence Hall Annual Reminder, which organizer Frank Kameny insisted all twelve male demonstrators attend in coat and tie, despite the heat, to show that “We aren’t monsters.” These Annual Reminder events, which continued until 1969, marked the first time in American history that people publicly assembled to demand equal rights for homosexuals. Kuromiya also continued his activism in the anti-war and civil rights movements. On Oct. 20 and 21, 1967, he participated in Abbie Hoffman’s organized attempt to levitate the Pentagon, protesting the Vietnam War.

In April 1968, Kuromiya instigated the largest antiwar demonstration in the University of Pennsylvania’s history, attracting thousands of people. Kiyoshi had printed and put up leaflets from a fictional group called the Americong that said there would be an “innocent dog” burned with napalm in front of the Van Pelt Library at Penn in “protest of the horrors of using napalm on humans” by US armed forces in Vietnam. Among those who showed up on behalf of the dog on April 26 were several dozen plainclothesmen from the Pennsylvania S.P.C.A., agents from the police commissioner's office and civil disobedience squad, reporters from television, radio, and press offices, four veterinary ambulances, and faculty and students—in all, about 2,000 people. That day's editorial in the University's student newspaper correctly surmised, “We expect, and certainly hope, that the threatened dog-burning is only symbolic, and will not be carried out.” The opinion piece noted that “more ire has been raised over the fate of one dog in one day than over the lives of the thousands of Vietnamese peasants who have been subjected to napalm bombs for the past three years.” (Indeed, the graduate chair of the Romance Languages department was quoted as saying, “I think it’s a dreadful idea to napalm a dog—it’s even worse than napalming children.”) On the day of the protest, Kuromiya handed out leaflets that said "Congratulations, you've saved the life of an innocent dog. How about the hundreds of thousands of Vietnamese that have been burned alive?"

Later that same year, Kuromiya designed, created, and printed the iconic “Fuck the Draft” poster, which depicted Bill Greenshields burning his draft card at the Levitate the Pentagon demonstration. Though he used the pseudonym Dirty Linen Corporation, his provocative advertisement—“The perfect gift for Mother’s Day” and “Buy five, and we’ll send a sixth one to the mother of your choice”—put a target on his back. Undeterred, Kuromiya continued to share the poster by disseminating 2,000 copies at the August 1968 Democratic Convention in Chicago. There, many protesters, reporters, and bystanders were met with unprecedented levels of police brutality and police violence by the Chicago Police Department, particularly in Grant Park and Michigan Avenue in Chicago during the convention. It was a night of unrestrained police violence against peaceful onlookers who just happened to be in the area and who had broken no laws, even as protestors chanted, “The whole world is watching.” Though then-mayor Richard Daley described the incident as the work of “professional trouble makers,” the actions by Chicago police, the Illinois National Guard, and other law enforcement agencies were later described by the National Commission on the Causes and Prevention of Violence as a "police riot". Kuromiya escaped the riot mostly unscathed, although the FBI arrested and charged him in Philadelphia under U.S. Code title 18, section 1461 of the postal code, which considered the poster an obscene, indecent, and crime-inciting work. He spent the next three years fighting his “Fuck the Draft” obscenity charge. It was eventually dismissed on June 7, 1971, in the Supreme Court case, Cohen v. California, which decided that the phrase was protected under freedom of speech.

Following the 1969 Stonewall Riots in New York City, Kuromiya co-founded the Gay Liberation Front with Basil O’Brien after attending a Homophile Action League meeting. The GLF was one of the more radical pro-gay political organizations to launch post-Stonewall, and had a significant proportion of African-Americans, Latinos, and Asians—though they were only a small group of about a dozen in 1969. At the time, Kuromiya wrote in the Free Press, “Homosexuals have burst their chains and abandoned their closets. We came battle-scarred and angry to topple your sexist, racist, hateful society. We came to challenge the incredible hypocrisy of your serial monogamy, your oppressive sexual role-playing, your nuclear family, your Protestant ethic, apple pie, and Mother.” In later years, he described the GLF’s tactics during this time as deliberately silly: “We’d go up to a line of cops with tear gas grenades and horses and clubs. And link arms and do a can-can. Really threw them off guard.” Unlike earlier gay rights groups of that time, GLF actively recruited a wide range of people and expressed solidarity with the Young Lords and the Black Panther Party. Kuromiya attended the 1970 Black Panther Party Convention in Philadelphia, representing GLF as an openly gay delegate, where he both introduced and received support for the gay liberation struggle. Also in 1970, Kuromiya attended Rebirth of Dionysian Spirit, a national gay liberation conference in Austin, Texas—an experience that changed the way he viewed the gay liberation struggle. In 1972, he created the first gay organization on the University of Pennsylvania campus, Gay Coffee Hour, which met every week on campus and was open to non-students and served as an alternative space to gay bars for gay people of all ages.

In 1974, Kuromiya was diagnosed with metastatic lung cancer, which he overcame in 1977 after having an upper lobectomy. A chance meeting with the acclaimed architect Buckminster Fuller resulted in the pair traveling around the world and co-writing six books together, until Fuller’s death in 1983. He assisted Fuller in writing Critical Path, which sketched a vision of a bountiful future created by technological advances. In what James Traub in The New York Times Book Review called “a bizarre and often revelatory volume,” the authors suggested that the blossoming of technology had the potential to end war.

Kuromiya began working earnestly on the AIDS movement once the AIDS epidemic began in America in the early 1980s, being most involved with the Philadelphia chapter of ACT UP (the AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power). After being diagnosed with AIDS himself in 1989, Kuromiya only intensified his advocacy work. He created the ACT UP Standards of Care, which was the first of its kind for people with HIV produced by people with AIDS. He approached his work with the motto "Information is power" and educated himself on AIDS issues to the point he was invited to participate in National Institutes of Health alternative therapy panels. This appointment came largely from his experience with medical marijuana, which he openly distributed to people living with AIDS through a medical marijuana buyers’ club called Transcendental Medication. As the lead plaintiff of a class-action lawsuit against the federal government’s prohibition of medical marijuana—Kiyoshi Kuromiya v. The United States of America—he argued marijuana provided relief against the side effects of early HIV medications and, for some people, was more effective treatment than existing medication. Though the Supreme Court decided against him in 1999, he continued to operate his dispensary.

Kuromiya founded the Critical Path Project newsletter, which brought Fuller’s strategies and theories to the struggle against AIDS. The newsletter, one of the earliest and most comprehensive sources of HIV treatment information, was routinely mailed to thousands of people living with HIV all over the world. Kuromiya also sent the newsletters to hundreds of incarcerated individuals to ensure their access to up-to-date treatment information. He was involved locally, nationally, and internationally in AIDS research as both a treatment activist and clinical trials participant, and he fought for research that involved the community in its design – particularly people of color, drug users, and women. He developed the newsletter into one of the very first websites on the public Internet, filled with the latest HIV/AIDS information. From there, the site became host to the Critical Path AIDS Project—through which Kuromiya operated a 24-hour hotline for anyone who sought his help and provided free internet access to hundreds of people with HIV in Philadelphia. According to transgender and health rights activist JD Davids, with whom he worked on this project, this was only possible because “Kiyoshi was one of those people who physiologically didn’t need to sleep.” Kuromiya was intensely stubborn, and Davids also credits him as instilling “in me that the importance of queer liberation is understanding not just that all people deserve equality, but that all of us bring something that can improve the rest of humanity.”

Kuromiya was also a leader in the struggle to maintain freedom of speech on the Internet. He went to the Supreme Court in 1997 in order to expand freedom of speech rights to protections of the circulation of sexually explicit information about AIDS on the Internet, which led to the court's striking down part of the Communications Decency Act. In his last act of civil disobedience, Kuromiya protested at the U.S. Trade Representative’s office on Oct. 6, 1999, seeking to stop the government from threatening sanctions against countries that were putting regulatory mechanisms in place to make generic HIV medication available at a low cost. He was horrified that transnational corporations, particularly pharmaceutical companies, were pushing to keep generic HIV drugs off the market at the expense of human lives.

When Kuromiya entered hospital with AIDS-related complications, he continued teaching people about the illness. “He’d say, ‘Does everyone understand? Do you have any more questions?’ That happened even on the day after his birthday, he never took a break, and then he died later that day,” on May 10, 2000, a day after his 57th birthday. (There has been some argument that Kuromiya died of cancer complications and not complications from AIDS, but most sources seem to indicate the latter was most likely.)

Kuromiya fought passionately against any form of limiting expression, although sometimes he did not acknowledge or seem to really understand the logical limit to this freedom for the sake of freedom. For example, he showed support for NAMBLA (North American Man/Boy Love Association) in the 1980s, which dismayed many of his fellow activists and certainly complicates his legacy. One can imagine that Kuromiya saw the group through the eyes of his own childhood sexual experiences, which he enjoyed, or because of his singular commitment to free speech.

Whatever his complicated ideas, what truly matters is what Kiyoshi Kuromiya did and accomplished. He fought for free speech, equal rights, and equal access to information for all. He fervently believed in peace and the betterment of humanity through the use of technology and knowledge. Even on his last day, he was fighting to share his knowledge with people who needed him.

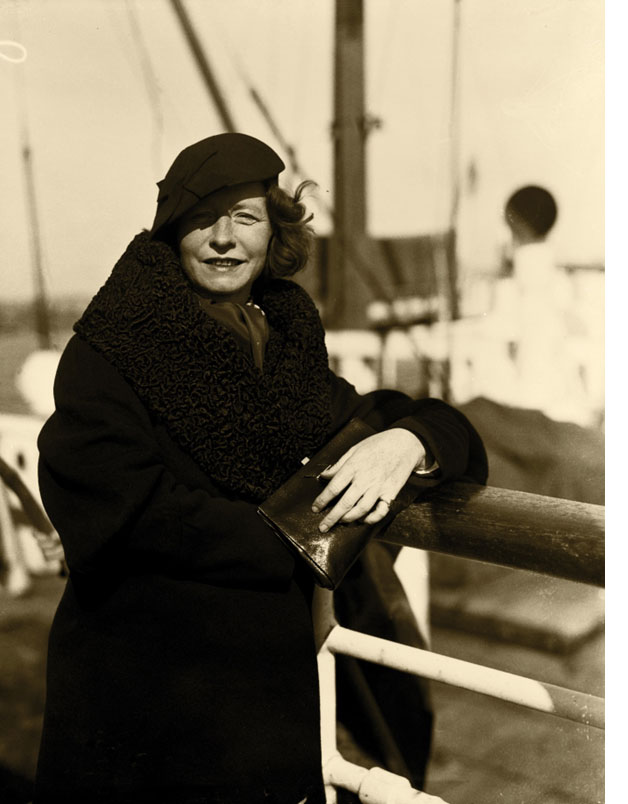

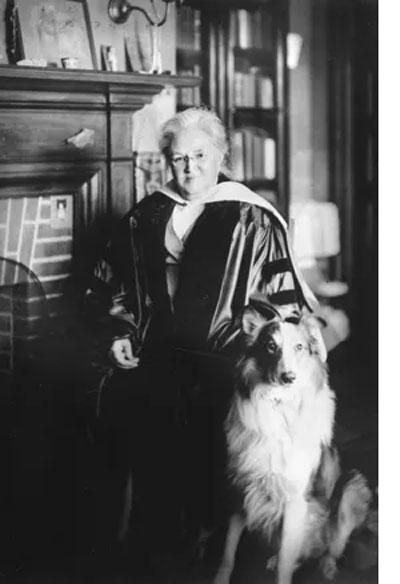

Edna St. Vincent Millay (February 22, 1892 - October 19, 1950) was a Pulitzer Prize- and Frost Medal-winning lyrical poet and playwright, renowned social figure, and noted feminist and social activist in New York City during the Roaring Twenties and beyond.

Millay was born in Rockland, Maine, on February 22, 1892. Her middle name was derived from St. Vincent's Hospital in New York City, where her uncle's life had been saved just before her birth. Throughout her lifetime, family and close friends often called her Vincent. In 1904, her parents officially divorced upon grounds of financial irresponsibility and domestic abuse, although they had already been separated for some years. Millay kept a letter correspondence with her father for many years, but he never re-entered the family. The family (mother, Cora, and her three daughters Edna, Norma, and Kathleen) moved from town to town, living in poverty. Cora traveled with a trunk full of classic literature, including Shakespeare and Milton, which she read to her children; she encouraged them to engage in music lessons, and she provided them with constant encouragement to excel. Millay recalled her mother’s support: “I cannot remember once in my life when you were not interested in what I was working on, or even suggested that I should put it aside for something else.” The family eventually settled in a small house on the property of Cora's aunt in Camden, Maine.

The three sisters were independent and outspoken, which did not always sit well with the authority figures in their lives. Millay's grade school principal, offended by her frank attitude, refused to call her Vincent. Instead, he called her by any woman's name that began with a V. Millay initially hoped to become a concert pianist, but because her teacher insisted that her hands were too small, she directed her energies to writing instead. At Camden High School, she began developing her literary talents, starting at the school's literary magazine, The Megunticook. At 14, she won the St. Nicholas Gold Badge for poetry, and by 15, she had published her poetry in the prominent children's magazine St. Nicholas, the Camden Herald, and the high-profile anthology Current Literature. The deeply-rooted New England traditions of self-reliance and respect for education, the Penobscot Bay environment, and the spirit and example of her mother from this difficult time became tremendous influences on Millay’s personality, politics, and poetry in later life.

Millay's fame began in 1912 when, at the age of 20, she entered her poem “Renascence” in a poetry contest in The Lyric Year. The backer of the contest, Ferdinand P. Earle, chose Millay as the winner before consulting with the other judges, who had previously and separately agreed that the winning poem had to exhibit social relevance, which “Renascence” did not. Under this criterion, Millay ultimately placed fourth. The press drew attention to the fact that the Millays were a family of working-class women living in poverty, and because the three winners were all men, some felt that sexism and classism were a factor in Millay's poem coming in fourth place. This controversy launched the careers of both Millay and the contest winner, Orrick Glenday Johns. Johns, who was receiving hate mail because of the controversy, publicly conceded that he thought her poem was the better one. Additionally, the second-prize winner offered Millay his $250 prize money. In the immediate aftermath of the Lyric Year controversy, wealthy arts patron Caroline B. Dow heard Millay reciting her poetry and playing the piano at the Whitehall Inn in Camden, Maine, and was so impressed that she offered to pay for Millay's education at Vassar College, which Millay entered in 1913 at age 21.

At the time, Vassar was exclusively for female students, and Millay called it a “hell-hole” due to its rigid expectations that its students be refined and live according to their status as young ladies. Before she attended the college, Millay had had a liberal home life that included smoking, drinking, playing gin rummy, and flirting with men and women alike. During her time at Vassar, she was a prominent campus writer, becoming a regular contributor to The Vassar Miscellany. While at school, she had several romantic relationships with fellow students, including Edith Wynne Matthison, who would go on to become an actress in silent films. At the end of her senior year in 1917, the faculty voted to suspend Millay indefinitely; however, in response to a petition by her peers, she was allowed to graduate.

After her graduation from Vassar in 1917, Millay moved to Greenwich Village in New York City, just as it was becoming known as a bohemian writer's haven. While living in New York City, Millay was openly and actively bisexual, developing many passing relationships with both men and women. In December of that year, she secured a part in socialist Floyd Dell’s play The Angel Intrudes, which was being presented by the Provincetown Players, a group with which she continued to work for several years. Millay soon began a love affair with Dell, one that continued intermittently until late 1918, and during which he proposed marriage and was refused. Millay published her first book, Renascence, and Other Poems, in 1917. Although sympathetic with socialist hopes “of a free and equal society,” Millay never became a Communist. However, her works reflect the spirit of nonconformity that imbued her Greenwich Village experience and relationships. Among her close friends during this period were the writers Witter Bynner and Susan Glaspell. In February of 1918, poet Arthur Davison Ficke, a friend of Dell and correspondent of Millay, stopped off in New York. At the time, Ficke was a U.S. Army major bearing military dispatches to France. When he met Millay, they fell into a brief but intense affair that affected them for the rest of their lives and about which both wrote sonnets. Millay’s were serially published in 1920 and then collected in Second April (1921). In many of these sonnets, she suggested that lovers should suffer and that they should then sublimate their feelings by pouring them “into the golden vessel of great song.” Fearful of being possessed and dominated, especially in a traditional marriage-based relationship, the poet disparaged, at least temporarily, human passion and dedicated her soul to poetry.

While living in Greenwich Village, Millay learned to use her poetry to support feminist activism. She also wrote short stories, which paid better than poetry, for Ainslee's Magazine, under the pseudonym Nancy Boyd. In 1919, she wrote the experimental poetic drama Aria da Capo, which played at the Provincetown Playhouse in New York City, starring her sister Norma. The one-act Aria portrays a symbolic playhouse where the play is grotesquely shifted into reality and those who were initially acting are ultimately murdered because of greed and suspicion, with the implication that the play's action would go on endlessly—da capo. Most critics called it an anti-war play, but it also expresses the representative and everlasting, like the Medieval morality play Everyman and the biblical story of Cain and Abel. For Millay, Aria da Capo represented a considerable achievement of which she always remained proud.

In 1920, Millay’s poems began to appear in Vanity Fair. Two of its editors, John Peale Bishop and Edmund Wilson, became Millay’s suitors, and in August, Wilson formally proposed marriage. Unwilling to subside into a domesticity that would curtail her career, Millay refused him. Her 1920 collection, A Few Figs From Thistles, drew controversy for its explicit exploration of female sexuality and feminism, and provided the basis for the so-called “Millay legend” of madcap youth and rebellion. She humorously and satirically expressed in Figs the postwar feelings of young people, their rebellion against tradition, and their mood of freedom symbolized for many women by the famously bobbed hair of the 1920s. The opening poem of the collection, “First Fig,” begins with the now-idiomatic line, “My candle burns at both ends.” Millay rejects prudence, respectability, and constancy in other poems of the volume, presenting the woman as an equal player in the love game and frankly embracing biological impulses in love affairs. “Rarely since Sappho,” wrote Carl Van Doren in Many Minds, had a woman “written as outspokenly as Millay.”

In his The Shores of Light: A Literary Chronicle of the Twenties and Thirties, Wilson noted the intensity with which Millay responded to every experience of life. That intensity used up her physical resources, and as the year went on, she suffered increasing fatigue and fell victim to a number of illnesses, culminating in what she described as a “small nervous breakdown.” Frank Crowninshield, another Vanity Fair editor, offered to let her go to Europe on a regular salary and write as she pleased under either her own name or as Nancy Boyd, and accordingly, she sailed for France on January 4, 1921. In Paris, Millay met and befriended the talented sculptor and famous lesbian expat Thelma Wood, sculptor Constantin Brâncuși, photographer Man Ray, and had affairs with journalists George Slocombe and John Carter, among other individuals. In March, she finished The Lamp and the Bell, her first verse drama, a five-act play commissioned by the Vassar College Alumnae Association for its fiftieth-anniversary celebration on June 18, 1921. Based on the fairy tale Snow White and Rose Red, The Lamp and the Bell was shrewdly calculated for the occasion: an outdoor production with a large cast, much spectacle, and colorful costumes of the medieval period. The play’s theme is friendship crossed by love, focusing on the love shared between women. In the end, integrity and unselfish love are vindicated.

Also in 1921, Millay became pregnant by a man named Daubigny. She secured a marriage license in Paris, but then returned to New England where her mother helped her induce an abortion with alkanet, as recommended in her old copy of Culpeper's Complete Herbal. Possibly as a result, Millay was frequently ill and weak for much of the next four years. In 1922, Millay returned to France, this time with her mother, a retreat during which Millay was supposed to complete “Hardigut,” a satiric and allegorical philosophical novel for which she had received an advance from her publisher. But, weakened by her ongoing illnesses, she did not finish the work, and the Millays returned to New York in February 1923.

Later that year, Millay met 43-year-old Eugen Jan Boissevain, the son of a Dutch newspaper owner, at a charades-playing party held at a mutual friend’s house. Boissevain was a businessman who had made his fortune by importing coffee from Java, and who had no literary pretensions whatsoever. Handsome, robust, adventurous, and quixotic, he was a widower, once married to feminist Inez Milholland, whom Millay had met during her time at Vassar. The two immediately fell in love, and, after Millay's refusing three more marriage proposals from other suitors, Millay wed Boissevain in July of 1923. A self-proclaimed feminist, Boissevain did not expect domesticity of his wife but was instead willing to devote himself entirely to the development of Millay’s talents and career. In addition, he assumed full responsibility for the medical care she needed and took her to New York for an operation the very day they were married. Millay famously described their marriage as being that they lived like two bachelors, having made an agreement that their marriage would be sexually “open.” Certainly, this was highly unusual in the 1920s. But this was indicative of Millay’s stubborn individuality and determination to do things in her own way. Both Millay and Boissevain had mtiple lovers throughout their 26-year marriage.

Millay won the Pulitzer Prize for Poetry in 1923 for The Ballad of the Harp-Weaver, a collection dedicated to her mother. She was the first woman to win the esteemed poetry prize, though two women (Sara Teasdale in 1918 and Margaret Widdemer in 1919) had previously won special prizes for their poetry prior to the establishment of the award. A carefully constructed mixture of ballad and nursery rhyme, the title poem of the collection tells a story of a penniless, self-sacrificing mother who spends Christmas Eve weaving for her son “wonderful things” on the strings of a harp, “the clothes of a king’s son.” Millay thus paid tribute to her mother’s sacrifices that enabled her to have gifts of music, poetry, and culture—the all-important clothing of mind and heart. Several of the collection’s poems speak out for the independence of women; others frankly portray both hetero and homosexuality; above all, the collection embodies and describes in new ways intimate female experiences and expressions. Also in the volume are seventeen “Sonnets from an Ungrafted Tree,” telling of a New England farm woman who returns in winter to the house of an unloved, commonplace husband to care for him during the ordeal of his last days. Critics regarded the physical and psychological realism of this sequence as truly striking. The poems abound in accurate details of country life set down with startling precision of diction and imagery.

Later in 1923, Millay, Evelyn Vaughn, William Rainey, and Reginald Travers commissioned famed scenic designer Cleon Throckmorton to convert an old box factory into Cherry Lane Playhouse, “to continue the staging of experimental drama.” Still in operation today (“the smallest stage in town [which] is asked to accommodate no end of enthusiastic performers), it is New York's longest continually running Off-Broadway theater. Cherry Lane Playhouse fueled some of the most ground-breaking experiments in the history of the American stage. The Downtown Theater movement, The Living Theatre, and Theatre of the Absurd all took root at the Playhouse, and it proved fertile ground for several of the 20th century’s most seminal dramatic voices.

By 1924, Millay was widely regarded as the finest living American lyric poet, but during this period her health faltered, with her suffering severe headaches and altered vision; despite this, she engaged in reading tours throughout the 1920s. Afflicted by neuroses and a basic shyness, she thought of these tours—arranged by her husband—as necessary ordeals, so she continued the readings for many years, and for many in her audiences her appearances were memorable. In 1925, Millay and Boissevain decided to leave New York for the country (Millay felt the city was too exciting and she needed quiet to write), so Boissevain gave up his import business, and in May he purchased Steepletop, a run-down, seven-hundred-acre farm in the Berkshire foothills near the village of Austerlitz, New York. They built a barn, a writing cabin, and a tennis court. Later, they bought Ragged Island in Casco Bay, Maine, as a summer retreat. The life and death, growth and decay of nature served Millay as an organizing principle both in her writing and in her life, and Steepletop became her sanctuary. She grew her own vegetables in a small garden, from which she derived considerable pleasure. Boissevain focused on his mission in the marriage, which he increasingly felt was to protect her from mundane tasks that would distract her from her writing.

Also in 1925, the Metropolitan Opera commissioned Deems Taylor to compose music for an opera to be sung in English, and he asked Millay, whom he had met in Paris, to write the libretto. She agreed to do so and began writing a blank verse libretto set in tenth-century England. The result, The King's Henchman, drew on the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle's account of Eadgar, King of Wessex. The opera began its production in 1927 to high praise; The New York Times described it as "the most effectively and artistically wrought American opera that has reached the stage.”

Later in 1927, Millay became involved in the Nicola Sacco and Bartolomeo Vanzetti case. On August 22, she was arrested, with many others, for picketing the State House in Boston, protesting the execution of the two Italian anarchists who had been convicted of murder. Convinced, like thousands of others, of a miscarriage of justice, and frustrated at being unable to move Governor Fuller to exercise mercy, Millay later said that the case focused her social consciousness, making her “more aware of the underground workings of forces alien to true democracy.” The experience increased her political disillusionment, bitterness, and suspicion, and it resulted in her article “Fear,” published in Outlook on November 9, 1927, in which she vehemently lashed out against what she saw as the callousness of humankind and the “unkindness, hypocrisy, and greed” of many elders; she was appalled by “the ugliness of man, his cruelty, his greed, his lying face.”

During one of her reading tours in late 1928, Millay read at the University of Chicago, where she met and struck up an affair with George Dillon, a student 14 years her junior. This relationship inspired the love sonnets of her 1931 collection Fatal Interview. Fatal Interview is similar to an Elizabethan sonnet sequence but expresses a woman’s point of view. Several reviewers called the sequence great, praising both the remarkable technique of the sonnets and their meticulously accurate diction. Fatal Interview and her relationship with Dillon juxtapose with her lingering bitterness from 1927, which appears in the collections Millay published before and after: The Buck in the Snow, and Other Poems (1928) and Wine from These Grapes (1934). The latter contains a notable eighteen-sonnet sequence, “Epitaph for the Race of Man.” The first five sonnets describe the disappearance of the human race. The second set reveals humans' activities and capacity for heroism, but also human intolerance and alienation from nature. In the sequence’s final sonnets, the eventual extinction of humanity is described, with will and appetite dominating.

During early 1936, Millay began serious work on a long verse poem, Conversation at Midnight, which she had been planning for several years. She was staying at the Sanibel Palms Hotel in Florida, on a writing holiday, when, on May 2, 1936, a fire started after a kerosene heater on the second floor exploded. Everything was destroyed, including the only copy of Millay's manuscript and a 1600s poetry collection written by the Roman poet Catullus. Upon her return to Steepletop, she would go on to rewrite Conversation at Midnight from memory and release it the following year. In the summer of 1936, Millay was riding in her and Boissevain’s station wagon when the door suddenly swung open, causing her to be thrown from the vehicle into a rocky gully. The accident severely damaged nerves in her spine and arms, requiring frequent surgeries and hospitalizations, and at least daily doses of morphine. In the aftermath of this accident, Millay lived the rest of her life as a partial invalid in constant pain, tended lovingly by Boissevain.

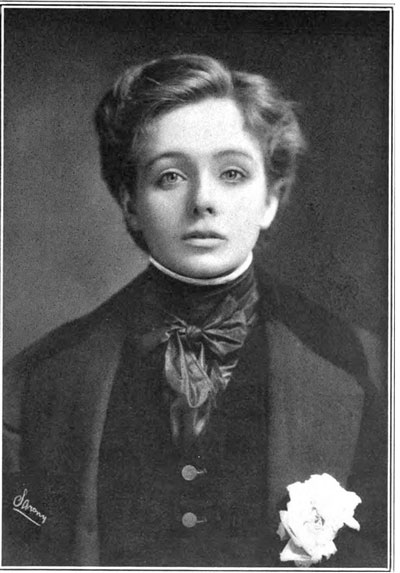

During World War I, Millay had been a dedicated and active pacifist; however, by 1940, she was sufficiently alarmed by the rise of fascism to write against it, advocating for the U.S. to enter the war against the Axis. She became an ardent supporter of the war effort. She later worked with the Writers' War Board to create propaganda, including poetry. With what she herself described in her collected letters as “acres of bad poetry,” she hoped to rouse the nation. Unfortunately, her war work irreparably damaged Millay's reputation in poetry circles.